Results from a recent study conducted by a team of researchers at the Oregon Health & Sciences University (OHSU), indicate that a specific peptide named ISP can penetrate heart attack scar tissue and restore cardiac nerves. The study, entitled “Targeting protein tyrosine phosphatase σafter myocardial infarction restores cardiac sympathetic innervation and prevents arrhythmias,” was published in the current issue of Nature Communications.

Results from a recent study conducted by a team of researchers at the Oregon Health & Sciences University (OHSU), indicate that a specific peptide named ISP can penetrate heart attack scar tissue and restore cardiac nerves. The study, entitled “Targeting protein tyrosine phosphatase σafter myocardial infarction restores cardiac sympathetic innervation and prevents arrhythmias,” was published in the current issue of Nature Communications.

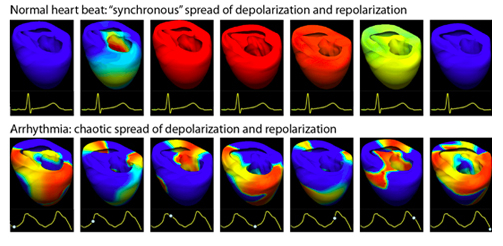

Survivors of myocardial infarction (MI) remain at high risk for cardiac arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. The infarct, or scar, generates an anatomical substrate that promotes re-entrant arrhythmias, and numerous studies indicate that altered sympathetic neurotransmission in the heart also plays a key role in the onset of post-infarct cardiac arrhythmias. Based on these clinical assumptions, Jerry Silver, PhD and colleagues at Case Western Reserve tested this new peptide called intracellular sigma peptide (ISP), with the aim of understanding if the compound could restore spinal cord function and potentially stop fatal arrhythmias after a heart attack.

With knowledge of Case Western Reserve’s tests, the researchers at Oregon Health & Sciences University (OHSU) led by Beth A. Habecker, PhD, tested the ISP and exceeded even Silver’s prospect. Habecker was able to achieve a remarkable 100 percent success in mice models.

“Essentially, the OHSU group cured arrhythmia in the mouse using ISP,” Silver said in a recent press release. “They observed true regeneration right back into the scar within the infarct area. This is pretty exciting.”

“When she discussed her work with me, I almost fell out of my chair,” Silver recalled in the news release. “I realized how similar our work was, and I said, ‘we have to send you our peptide.’ When I described the peptide, she said she wanted to give it a try in heart attack research in animal models.”

The study conducted by Habecker and colleagues at OHSU used the compound provided by Silver’s team. The researchers forced a heart attack in mice and subsequently gave the mice ISP, saline of another peptide (to the controls). Then after 2 weeks, the researchers observed that those mice that received ISP were able to restore their sympathetic cardiac nerve function through the left ventricle. Furthermore, there were no arrhythmias in these mice. However, the mice that received saline or the other peptide presented a lack of nerve function in the cardiac sympathetic areas that damaged by the forced heart attack. Consequently, these mice presented the myocardial infarction, arrhythmias.

“My role was that of a supplier,” Silver said in the press release. “It was really important that this study of the peptide be conducted without my involvement. The study at OHSU provided independent validation that the peptide works in animals. And it confirmed the effectiveness of ISP in a completely different model — heart attack. That kind of replication is rare.”

These findings are encouraging, and ISP can potentially be developed to prevent arrhythmias after a heart attack. “We are extremely fortunate to have the connection with Dr. Silver’s lab, which allowed us to test a systemically available therapeutic in our heart attack model,” Habecker explained in the press release. “The fact that giving ISP several days after injury can fully restore innervation and decrease arrhythmia risk is amazing, and is a key finding.”

The researchers are now going to test the ISP peptide action after a heart attack in larger animals, in order to reveal the optimal tolerated dose, toxicity and amount of peptide that can potentially infiltrate scar tissues. Moreover, the researchers are aiming at understanding if the peptide can be given after large amounts of time following a heart attack providing similar benefit as in the first post-heart attack.

“We want to do clinical trials here at Case Western Reserve with ISP when it reaches clinical trial stage,” Silver said in the press release. “We could conduct those trials in collaboration with OHSU and other centers throughout the country.”