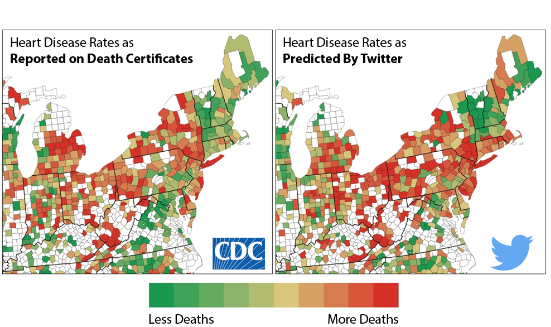

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania have discovered that monitoring traffic on the social networking service Twitter, in addition to its proven capacity to break and cover emerging news stories, contribute to overthrow of governments, launch social movements, and start or end careers, can also be used to evaluate a community’s psychological wellbeing and to even predict heart disease rates.

Previous studies have identified many factors that contribute to the risk of heart disease: traditional ones, like low income or smoking but also psychological ones, like stress. The Penn researchers have demonstrated that Twitter can capture more information about heart disease risk than many traditional factors combined, since it also characterizes the psychological climate of communities.

The Penn researchers found that expressions of negative emotions such as anger, stress and fatigue in tweets originating in a particular county were indicative of higher heart disease risk in that area. Conversely, positive emotions like excitement and optimism expressed on Twitter were associated with lower risk of those diseases.

While scientists have long suspected that a climate of psychological wellbeing in communities is a key factor in maintaining general physical health among their residents, it is difficult and costly to assess on a large scale and measure scientifically using conventional methods. However, the Penn researchers propose that employing Twitter postings as a window into a community’s collective mental state may provide a useful tool in epidemiology and for measuring the effectiveness of public-health interventions.

The study, published online before print in the journal Psychological Science, entitled “Psychological Language on Twitter Predicts County-Level Heart Disease Mortality” (January 20, 2015, doi: 10.1177/0956797614557867), was led by Penn School of Arts & Science’s Department of Psychology graduate student Johannes Eichstaedt, and also included H. Andrew Schwartz, a visiting assistant professor in the School of Engineering and Applied Science’s Department of Computer and Information Science; Lukasz A. Dziurzynski, Maarten Sap, Christopher Weeg, and Emily E. Larson of the Penn Department of Psychology; Margaret Kern, an assistant professor at the University of Melbourne’s Graduate School of Education in Australia; Gregory Park, a postdoctoral fellow in the School of Arts and Science’s Department of Psychology; Darwin R. Labarthe of Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine; Raina M. Merchant of Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine; Sneha Jha, and Megha Agrawal of the Penn Department of Emergency Medicine;Lyle Ungar, a professor in the Penn Department of Computer and Information Science, and director Martin Seligman, of the Penn Positive Psychology Center,

The study, published online before print in the journal Psychological Science, entitled “Psychological Language on Twitter Predicts County-Level Heart Disease Mortality” (January 20, 2015, doi: 10.1177/0956797614557867), was led by Penn School of Arts & Science’s Department of Psychology graduate student Johannes Eichstaedt, and also included H. Andrew Schwartz, a visiting assistant professor in the School of Engineering and Applied Science’s Department of Computer and Information Science; Lukasz A. Dziurzynski, Maarten Sap, Christopher Weeg, and Emily E. Larson of the Penn Department of Psychology; Margaret Kern, an assistant professor at the University of Melbourne’s Graduate School of Education in Australia; Gregory Park, a postdoctoral fellow in the School of Arts and Science’s Department of Psychology; Darwin R. Labarthe of Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine; Raina M. Merchant of Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine; Sneha Jha, and Megha Agrawal of the Penn Department of Emergency Medicine;Lyle Ungar, a professor in the Penn Department of Computer and Information Science, and director Martin Seligman, of the Penn Positive Psychology Center,

In their paper, the coauthors report that they used language expressed on Twitter to characterize community-level psychological correlates of age-adjusted mortality from atherosclerotic heart disease (AHD). They note that language patterns expressed in tweets reflecting negative social relationships, disengagement, and negative emotions — especially anger and use of words such as “hate” or expletives — emerged as cardiovascular disease and mortality risk factors, even after variables like income and education were adjusted for. On the other hand, attitudes indicative of underlying optimism, positive emotional language, and psychological engagement expressed using words like “wonderful” or “friends,” were observed to be protective factors against developing heart disease.

A cross-sectional regression model based only on Twitter language also predicted AHD mortality significantly better than a model combining 10 common demographic, socioeconomic, and health risk factors, including smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and obesity.

The scientists conclude that capturing community psychological characteristics through social media is feasible and demonstrable, and that these characteristics are strong predictors of cardiovascular mortality at the community level.

A Penn release notes that with billions of users tweeting daily about experiences, thoughts and feelings, the social media cyber-environment represents a new frontier for psychological research, and that data collected could be proven an invaluable public health tool if this information can be linked to real-world outcomes. Mindful of that, researchers from the World Well-Being Project have for some time been studying how measurably expressive online language usage is of inner thoughts and feelings.

Because there is no known means of directly and objectively measuring the workings of peoples’ inner emotional lives, the research team drew heavily on traditions in conventional psychological research analyzing words people use in speaking or writing, with earlier research by the group having shown that such linguistic analysis can work as efficiently as, or even better than traditional questionnaires for assessing a person’s personality traits.

“Getting this data through surveys is expensive and time consuming, but, more important, you’re limited by the questions included on the survey,” Mr. Eichstaedt observes. “You’ll never get the psychological richness that comes with the infinite variables of what language people choose to use.”

Having observed correlations between language and the emotional states of users, the researchers investigated whether they could demonstrate linkage between persons’ emotional states and physical outcomes associated with them — coronary heart disease, the leading cause of death worldwide being an ideal candidate for study.

“Psychological states have long been thought to have an effect on coronary heart disease,” says Dr. Kern. “For example, hostility and depression have been linked with heart disease at the individual level through biological effects. But negative emotions can also trigger behavioral and social responses; you are also more likely to drink, eat poorly and be isolated from other people which can indirectly lead to heart disease.”

“Psychological states have long been thought to have an effect on coronary heart disease,” says Dr. Kern. “For example, hostility and depression have been linked with heart disease at the individual level through biological effects. But negative emotions can also trigger behavioral and social responses; you are also more likely to drink, eat poorly and be isolated from other people which can indirectly lead to heart disease.”

The researchers note that since it is such a common cause of early mortality, public health officials are keenly interested when heart disease is identified as the underlying cause on death certificates, and collect painstaking data regarding potential risk factors, such as rates of smoking, obesity, hypertension and lack of exercise. With this sort of data available on a county-by-county level in the United States, The Penn research team set about matching this measured physical epidemiology with their digital version based on Twitter postings.

Image Courtesy University of Pennsylvana

Using data from a set of public tweets made between 2009 and 2010, the Penn researchers employed established emotional dictionaries, along with automatically-generated word clusters reflecting behaviors and attitudes, in analyzing a random sample of tweets made by individuals who revealed their geographic locations There were enough tweets and health data available from about 1,300 U.S. counties, containing 88 percent of the country’s population to conduct correlative analyses.

“The relationship between language and mortality is particularly surprising,” says Dr. Schwartz, “since the people tweeting angry words and topics are in general not the ones dying of heart disease. But that means if many of your neighbors are angry, you are more likely to die of heart disease.”

“The relationship between language and mortality is particularly surprising,” says Dr. Schwartz, “since the people tweeting angry words and topics are in general not the ones dying of heart disease. But that means if many of your neighbors are angry, you are more likely to die of heart disease.”

These findings fits into existing sociological research suggesting that combined characteristics found in communities can be more predictive of physical health than the reports of any one individual.

“We believe that we are picking up more long-term characteristics of communities,” Dr. Ungar notes. “The language may represent the ‘drying out of the wood’ rather than the ‘spark’ that immediately leads to mortality. We can’t predict the number of heart attacks a county will have in a given timeframe, but the language may reveal places to intervene.”

“We believe that we are picking up more long-term characteristics of communities,” Dr. Ungar notes. “The language may represent the ‘drying out of the wood’ rather than the ‘spark’ that immediately leads to mortality. We can’t predict the number of heart attacks a county will have in a given timeframe, but the language may reveal places to intervene.”

Other potential limitations on the tweet analysis method’s predictive power include social factors influencing the sort of subject matter people choose to share on Twitter.

“If everyone is a little more positive on Twitter than they are in real life, however, we would still see variation from location to location, which is what we’re most interested in,” Dr. Schwartz explains.

Such variations could be used to analyze evidence of public-health interventions’ effectiveness at the community level, rather than on individual levels, since the team’s findings indicate that these tweets are aggregating information about people that can’t be readily accessed in other ways.

“Twitter seems to capture a lot of the same information that you get from health and demographic indicators,” Dr. Park says, “but it also adds something extra. So predictions from Twitter can actually be more accurate than using a set of traditional variables.”

“Twitter seems to capture a lot of the same information that you get from health and demographic indicators,” Dr. Park says, “but it also adds something extra. So predictions from Twitter can actually be more accurate than using a set of traditional variables.”

The Penn researchers’ study was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Templeton Religion Trust.

Sources:

University of Pennsylvania

Psychological Science

Image Credits:

University of Pennsylvania